The Invisible Art of Scent and Sound

By Deniz Ataman: journalist and UPA student

My No.2 pencil is the instigator of this essay on scent and sound. Knowing well that this is going to take me twice as long to complete from handwriting each word to transcribing on to a digital medium, writing in pencil is my tried-and-true analog method since I first learned how. My computer has its own scent and sound (a sighing, whirring and clicking sound mixed in with the scent of metallic chlorine) but my sensory experience with a pencil offers a warmth that a keyboard lacks. The smell of a sharpened pencil—woody, metallic and musty—complements the scratching, scribbling sound of lead on paper. The eraser rubs away the sentence replacing this one, which emits a dusty rubber scent with a soft, wooly sound reminiscent of a record on a turntable. These distinct sensory combinations, invisible and humble, have the power to transport me to days of nostalgia despite the constrictions my current reality.

How Smell Works (Or As Far as We Know)

Smell and sound trigger memories and emotions which are located in the brain’s amygdala. The science behind sound is well understood and concrete: a series of perceptible and imperceptible vibrations stimulate nerve endings in our primary auditory cortex to create sound we can perceive. Whereas the mechanisms in our olfactory system are still relatively unknown, despite some headway in research. In 2004, the Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine was awarded to Linda S. Buck and Richard Axel for their research on odorant receptors and the olfactory system. Their theory looks at a family of genes (about a thousand different genes or three percent of our genes) that can trigger the equivalent number of olfactory receptors. Basically, their research is an extension of the widely recognized molecular shape and receptor theory. Think of a lock and key – the right molecular shape fits in a receptor to unlock the perceived sense (used in a lot of drug research too).

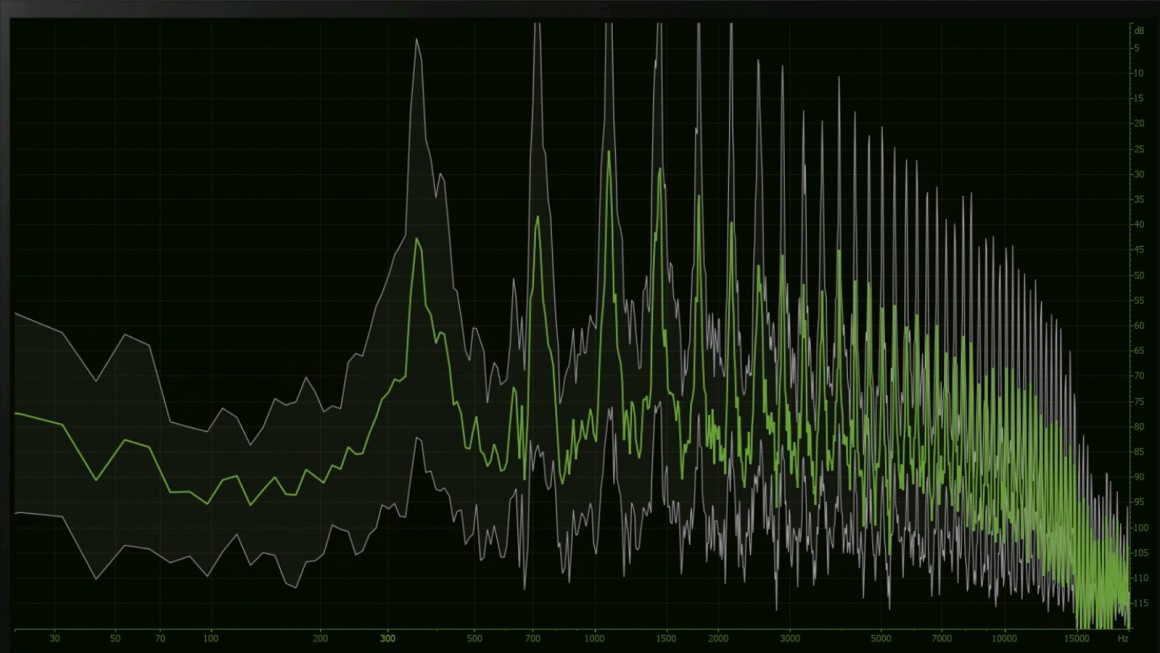

Another theory, (albeit controversial) the vibrational theory, was postulated famously by biophysicist Luca Turin. Rather than the lock and key theory, Turin looked at the vast number of odorants in the world as his key rebuttal: with a massive number of odorants in the world, our noses would require more receptors than we have, he theorized. Instead of focusing on a molecule unlocking a receptor to perceive smell, Turin turned to vibrations. His research theorized that our olfactory system processes smell as a vibration, just like sound.

Conducting an Auditory Scent, Is it Possible?

G.W. Septimus Piesse described scent as an invisible art form in his 1857 book, The Art of Perfumery. The same can be said of sound. Scent and sound’s intangible, emotionally evocative and ambient power are continued areas of research in both the commercial and art worlds. Turin explored this relationship in an experiment where he computed the vibrational composition of vanilla. He worked with a musical composer who translated those vibrations into musical notes, which were then performed by a symphony. According to Turin’s theory, the frequency of a scent molecule will correlate to a “high” or “low” note. The synesthetic language between scent and sound is nothing new. In Piesse’s book, he creates a “Gamut of Odors,” which assigns musical notes to an odor (i.e. a = lavender, b = peppermint, etc), offering a musical language to perfumery of blending top, middle and base notes.

So, according to a combination of Turin and Piesse’s work, base notes—such as vanilla emit longer frequencies—translate to a lower sound; conversely a top note’s frequency, like mint, would be steep and narrow, emitting a higher sound. However, if the orchestra emitted a vanilla scent during the performance, then his theory would be concrete, and we’d have some interesting dance parties. Olfactory research—despite significant discoveries in recent years—is still in its infancy.

However, the art and science of perfumery—the blending of fragrance materials (natural and/or synthetic) for various applications—took nods from music during the composition process.

Mandy Aftel, a pioneer in natural perfumery, compares scent and sound in her book, Essence and Alchemy:

“ …classical perfumers did acknowledge that a perfume oil is not a single scent but a complexity of scents that interact with one another in unpredictable ways, the equivalent of notes to a musician…” (p.135)

The fragrance industry today works with natural and synthesized materials for consumer products all over the world. Everything from fine fragrance to soaps, candles, laundry detergent, cleaning products, personal care products are created by perfumers. If you have a favorite scented product, take a moment to smell it like you would listen to a song: with intention and concentration. See if you can smell and visualize the top, middle and base layers.

Synesthesia and Creativity

In terms of artistic creation, the synesthetic bond between scent and sound brings to question: how do you create a track to evoke the different layers in a scent? For example, let’s think about vanilla again according to Turin’s research and Piesse’s octave of odors. In perfumery, vanilla is used as a base note. I would describe it as having a round shape and a warm (scent) note; how would that round shape and warmth translate in a sound? Probably similar to how synths work today with a base signal of a sine wave.

Whether one acknowledges the vibrational or the molecular shape theory in olfaction, it’s safe to say that the smell of something is never static. Just like sound, there are layers of information in a smell to be discovered by ourselves and from advanced computational devices. And as artists and engineers, we’re only as innovative as the tools we have. In terms of olfaction, a myriad of molecules lay undiscovered simply because these complex measuring devices have limitations on what can be detected (and they’ve gotten pretty far in the last century!). Both scent and sound hold immense power on how we experience and impact ourselves and our surroundings – take it from my No.2 pencil.

Resources:

Leave a reply